A close reading of the budget

By Forrest Cookson

Two major issues of the national budget were analyzed: the fiscal policy implied by the budget and the impact on inflation and the budget’s treatment of the financial sector.

World Environment:

In discussing the budget, we make the following assumptions:

- The inflation in the advanced countries will continue through 2023 slowing down during 2024. This inflation is a combination of the extraordinary levels of demand created during the pandemic; the disruption of the supply chains due to the Pandemic and the Ukraine war; the low-interest rates that had been maintained since the financial crisis of 2007; the consequences of the impact on oil, natural gas, coal, wheat, edible oil, and fertilizer of the Russian invasion of Ukraine; and the sanctions placed on Russia by the advanced economies. The difficulties in dealing with the current inflation are not really known as the situation facing the major central banks is unique. There are many ideas about the evolution of the inflation. This article takes a rather pessimistic view that the inflation will continue for two years through FY23 and FY24.

- Recession in the advanced economies: The actions by the major central banks to reduce the inflation rate are very likely to cause a recession in the advanced economies. I think that this is almost certain to happen: Already the US economy is contracting and the German economy is likely to decline in the present quarter. If, as I believe but unfortunately, modest increases in the interest rate by the major central banks will not reduce inflation; the necessary increases will trigger a recession. This will weaken the demand for Bangladesh exports, slowing the economy.

- The third development of the world economy will be the rising cost of capital as interest rates are increased too much higher levels. Access to capital from foreign sources will be quite expensive.

- The relationships of Russia and China with the advanced economies [USA, Canada, Germany, Japan, S. Korea, France, Italy, UK, other EU]. This relationship is deteriorating rapidly with unknown consequences for the rest of the world. This raises uncertainty and makes investors more cautious.

All four of these factors have negative impacts on Bangladesh: The inflation of import prices has placed great pressure on the balance of payments; the coming recession is already impacting the RMG markets and there is no idea of the depth and extent; the cost of capital combined with the uncertainties of the world economy will make the foreign investment much more difficult to attract to Bangladesh; finally the looming conflicts in Asia and Eastern Europe are foreboding. Increasingly people will run for safety rather than focusing on achievements. “Survival” rather than “growth” may be the motto.

The international environment that Bangladesh must manage during the period of FY23 and FY24 is dire. The two targets of GDP growth and reduced inflation are difficult and very risky if the Government is serious about achieving such an outcome.

Targets:

The targets set in the Budget are a 7.5% growth of GDP and a 5.7% inflation rate. The inflation rate is not defined so we take this as the CPI and adjust the target GDP [nominal] using the relationship between the CPI and the GDP deflator.

Review of the macroeconomics of the budget:

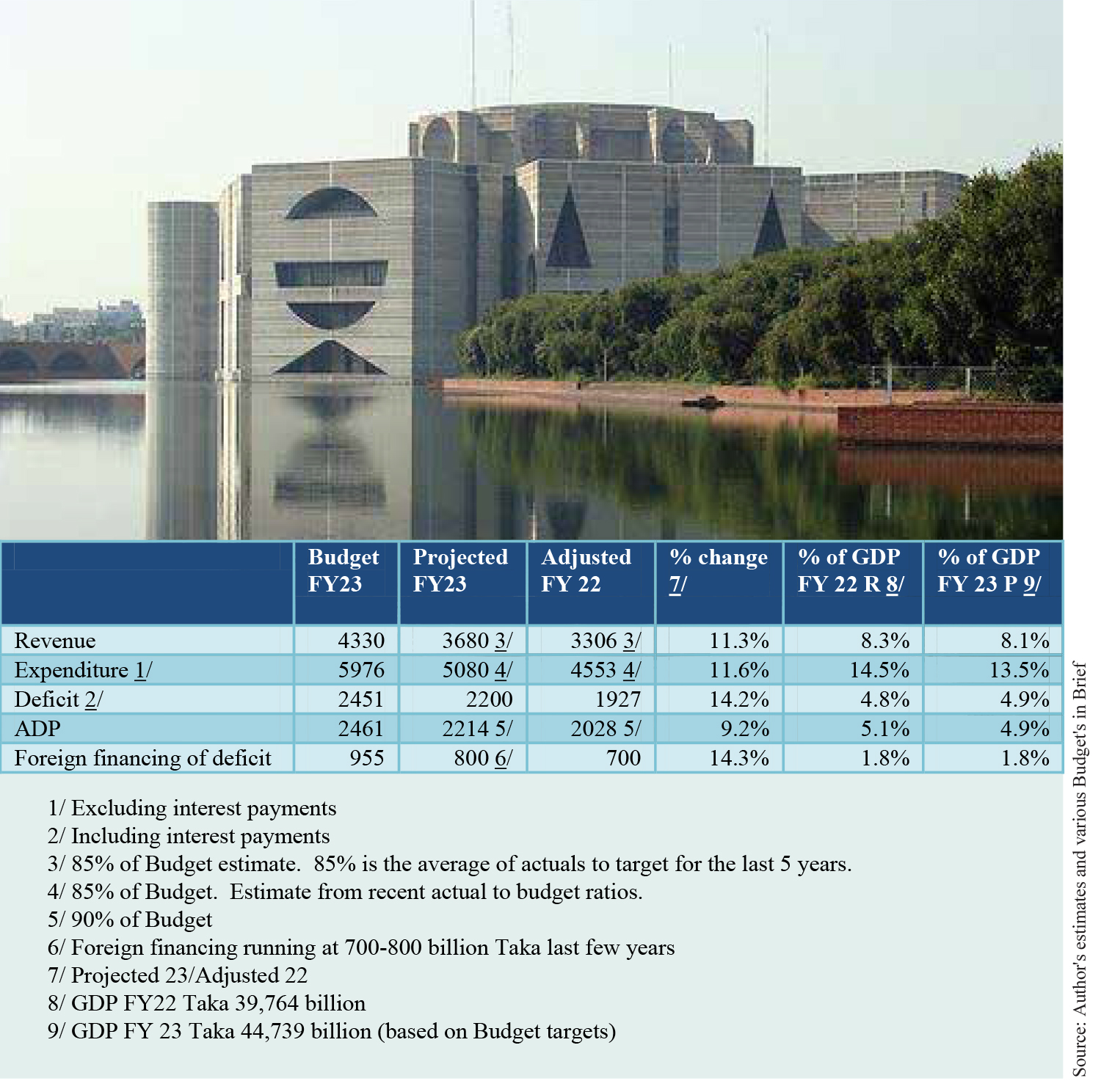

In this review, we estimate the final outcomes of the FY22 and FY23 budgets and briefly comment on the significance assuming that the targets of the budget are achieved. The results are presented in Table 1.

For FY22 we adjust to establish final outcomes based on past relationships between actuals and available data usually for 9 months of FY22. For FY23 we adjust the budget based on relationships to actuals in the past. We assume that the appropriate price deflator is 6%. The target nominal GDP for FY22 is Taka 39.8

trillion; for FY 23, Taka 44.7 trillion.

Revenues are projected to increase by 11.3 %, in FY23. In real terms, this is less than the target GDP growth rate and underscores the relatively modest expectations for revenue growth. The effect of this is to reduce the revenue to GDP ratio from 8.3% in FY22 to 8.1% in FY 23. One should interpret this as the budget will not make any progress in raising the revenue ratio. We also note that subsidies are about 1.9% of GDP in FY 22 and I expect the subsidies to increase to 2.2 % of GDP in FY23.

This implies that the revenues net of subsidies will decline from 6.4% of GDP in FY 22 to 5.9% of GDP in FY 23. This is not a sustainable position.

The expenditures of the Government net of interest payments are estimated to increase by 11.6%, increasing by 5.3% in real terms. In FY 23 expenditures decreased to 13.5% of GDP from FY 14.5% in FY22.

The deficit increases 14.2% but remains under 5% of GDP.

We estimate the ADP increases 9.2% in nominal terms or 3% in real terms.

The best measure of the impact of the budget on inflation is the extent to which the budget is financed by domestic borrowing. If one runs a large deficit but finances it by borrowing in foreign currency then there is in the short run little inflationary impact on the economy. The domestic financing of the budget is essentially the same in both FY22 and FY23. We conclude that from the fiscal policy standpoint the FY23 budget is not more restrictive than the previous year. That is there is no greater policy to contain inflation in FY23 than there was in FY 22.

The differences between FY 22 and FY23 are not great but it is clear that the authorities have not taken any major effort to control inflation.

There is a great deal of discussion about what the inflation rate is; all seem to doubt the BBS estimates. Like magic, Bangladesh has moved from a country with an inflation rate rather high at 5.5-6% to a country with one of the low inflation rates! The BBS inflation rate estimate is not credible. The street opinion is that prices are rising more rapidly than in recent years; careful work by the Center for Policy Dialogue indicates large increases in key food prices that make up much of the diet.

The Government is not able to control prices by setting price limits. The authorities see so-called hoarders as criminal and arresting such persons actually increase hoarding and make price increases greater.

The correct response to limiting inflation is to shift to restrictive monetary and fiscal policies. The simplest measure of the expansionary impact of fiscal policy is the deficit-financed by domestic borrowing. This shifts resources from saving by the private sector to spend by the Government. It does not matter much whether this comes through bank financing of the Government, private organizations increasing their holding of Government securities, or purchase of saving certificates, resources that would be saved are now spent. The only way this can be avoided is if the interest rates are raised on Government securities to attract savings that otherwise would be kept in other assets. In this case, there are fewer resources available for the private sector but no increase in aggregate demand. But normally one can expect that an increased deficit financed by domestic resources will increase aggregate demand and increase inflation.

As the deficit-financed by domestic borrowing is not much different the conclusion is that the macro-economic structure of the budget suggests that there will be little reduction of the inflation rate from this source. This is not really a surprise. The standard belief of macroeconomists is that it is monetary policy that will have the greatest impact on inflation. To use fiscal policy to contain inflation there are two possible directions: Raise taxes and reduce government expenditures. Governments are reluctant to do either and certainly not both! Our analysis of the budget is that it is neutral.

Financial Sector in the Budget:

When we turn to the Budget’s policies related to the financial system we find that the principal proposed action is highly inflationary. The key position of the Government is that interest rate policy will remain as is. The current policy is to cap lending rates at 9% and insist the fixed deposit rates are high enough to cover inflation. At present tax rates, and lending rates are negative. That is it costs the borrower nothing in real terms. As inflation is likely to increase during the next year the interest rate dynamics become more and more serious. The demand for lending will keep on rising. Saving will be less and less attractive. Thus in the midst of the inflation, interest rates in real terms are falling raising the demand for loans. Similarly, discouraging saving and encouraging consumption. All of this has an immediate and direct impact on rising inflation. The only monetary policy action that is left is to increase the cash reserve requirement and the statutory liquidity requirement to slow down lending and reduce the growth of the money supply. This of course leads to less credit to the private sector and a slowing of the economy. This approach uses the awkward instrument of limiting total lending but with negative lending rates, there are loan applications everywhere.

The budget introduces a neutral fiscal policy with no restraint on inflation and encourages a monetary policy that will either lead to increased inflation or reduced growth. In addition, the commercial banks will experience falling profits, difficulties in maintaining their capital requirements, and sharp falls in their share prices. There are plenty of problems in maintaining sound governance in the banking system. The situation towards which the private banks are headed will encourage illicit activities, selecting borrowers on the basis of rewards to the bankers or one’s chums or just guessing who to give a loan. The reduced quality of loans always leads to slower economic growth.

There is one out of all of this. The balance of payments situation is not really covered in the budget but one can reduce inflation and maintain the imports needed for economic growth by simply using the reserves to make the Taka stronger and meet the dollar requirements. Of course, after three or four years there will be no reserves left and another approach will be needed.

There is only one realistic way forward: Raise interest rates, let the Taka continue to float, and accept that the economy will slow. Concentrate on three things: Improve the revenue collection in an orderly way; encourage and build export industries both expanding the garment sector and building new sectors; and follow frugal government expenditure policies. After two or three years the economy will be able to expand into a stronger world economy. Or if the world economy is weak, against Bangladesh’s interests, it will be possible to continue to build the country albeit at a slower pace. The enormous success of the past 15 years was built on good policies and a favorable world economy. One cannot be sure that such conditions will return and continue. That is why extreme caution is needed and recognition by every country that one must be ready for a different, difficult world that none of us want.

Bangladesh faces tremendous inflationary pressures from world prices rising as they are now; from a rising balance of payments deficit forcing a depreciation of the currency and further increase of prices; and from the threat of a world recession harming the export markets and placing more pressure on the exchange rate.

The use of fiscal policy to fight inflation is not a very promising approach in any country. The Minister of Finance deserves credit for producing a budget that is neutral with respect to inflation. This is a tremendous achievement that few countries have managed. But a neutral fiscal policy is like not throwing kerosene on a raging fire. To put out the fire requires a monetary policy. On this point, the current policies must change. Without letting Bangladesh Bank implement a restrictive monetary policy the flames will just get hotter.

Forrest Cookson is an economist who has served as the first president of AmCham and has been a consultant for the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.