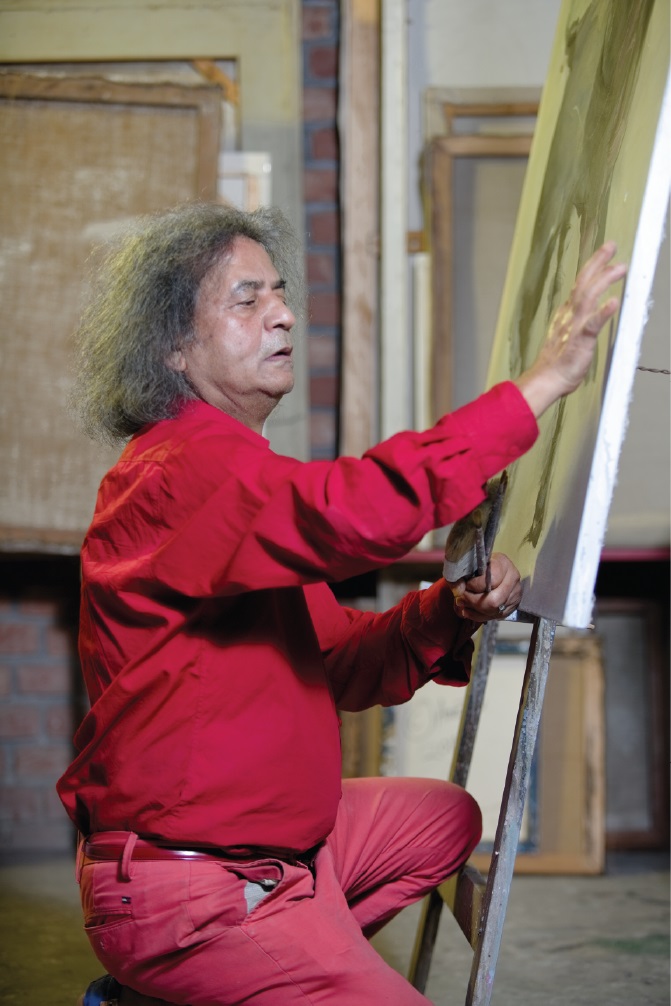

A NATIONAL ICON – Shahabuddin Ahmed at 69

A figurative painter, Shahabuddin Ahmed shot to fame in the post-independent Bangladesh. Today, with his one foot in Dhaka and the other in Paris, he embodies the unbound spirit of Bengal and the artistic outburst that redefined the art scene in many ways in the wake of the emergence of a new country. Colors celebrates his art and life on his 69th birthday.

1

Shahabuddin Ahmed, the country’s ace painter, also a freedom fighter, still exudes a kind of optimism which one can unfailingly link to the newly emerged country after a nine-month-long war in 1971. He seems unfazed by the afflictions that have so far plagued Bangladesh since its independence. In person, Shahabuddin comes off as something of an enigma – a national figure with the soul of a man-child. A soon to be septuagenarian (he is sixty-nine) Shahabuddin retains his youthful vigor to this day and happily flaunts his bountiful hair, though not to convey ‘hippiness’. Bedecked in a red shirt and khaki pants, he explains the reason why in most occasions he wears red, ‘I find European weather depressing, this is one way of beating the gloom. My other point is that if the Americans can wear their flag as accessories, including underwear, why can’t we be allowed to wear the colors of our own flag. So, as a freedom fighter I took to wearing red?’

Shahabuddin’s face, always animated and ready to crack a smile, seems imbued with a sense of ease and confidence. In his medium but poised frame, he reflects the power of an Alpha male that he is. As an artist he has made a name for himself by transmitting this very characteristic into his canvases and turning the humans he paints to “representing the ‘universal’ human motif.”

For a man who turned 69 on September 11, 2018, Shahabuddin Ahmed looks a lot younger. As the maestro dwells on his years of success, he does so with an air of lightness rare among the Bengali cognoscenti. If most would prefer to sink into a soporific rumination of their golden past, Shahabuddin is assailed by a certain sense of dissatisfaction. “You never know where a painting will take you and whether you would be able to continue painting till your last breath,” he says.

At times, uncertainty about the act of painting seems to confound him, as is the case with all geniuses. “At this age,” he proclaims, “the challenge is whether the next painting would be as good as the last one.” one realizes that candidness comes naturally to him. “Anyone can attempt what can be easily accomplished. One must stay focused on what is difficult to do. Always try something difficult, that’s my motto,” Sahabuddin philosophizes with a smile.

He still exudes the vigor of a youth as does all his creations. In real life, emotion is what he values most. In painting, “automatism” is the word he uses to explain his creative process. “If you do not have emotion, mere calculation will not guide you to a good painting. That is the difference between a Mondrian and a Picasso. Picasso didn’t control his emotion and he could bring a strong sense of emotion to his work. His is a “direct attack”, which is difficult to manage. But when this strategy is successful, it can really appeal to the heart. That is “humanity”,’ he explains.

2

The romancing of the male bodies we encounter in his paintings, showing the scampering Alpha males in their flight to an unknown destination, and the intermittent woman figures besides portraits of political leaders that he falls back upon to address history — all this is associated with a sense of ‘humanity’ he so passionately frames sitting in his studio at Kalabagan. These figural motifs associated with his universal idea of humanity made him what he is today – an icon of the art world.

He basks in the glory of the two-fold appeal — one that of an artist and other a freedom fighter. The maestro believes that his popularity stems from both of these roles. The love and respect showered on him on the occasion of his recent birthday anniversary, which was celebrated at the national level and was organized by Shilpakala Academy with the support of the birthday celebration committee, proves his point.

As for the humans he represents, the mythic dimension undoubtedly springs from his belief in the painter’s responsibility to produce a re-contextualized reality. “If you think you would represent human, forget where he is from … that human becomes universal. They may be black or white … but in my painting there are no white or black men, they are all humans,” he points out. And that is where the strength of any good Shahabuddin rests.

Looking at a huge half-done expressionistic canvas hung on the back wall of his studio, one realizes that the maestro captures the human figures in flight across an unrecognizable space in an indeterminate time. This, perhaps, is a way for the artist to envision his protagonists as denizens of an emergent reality, rather than as humans trapped in an actual space, chained to its social relations.

‘I remember attending an anatomy class one day. Immediately after that, I said to myself, why do I need to do this! I decided to use the mirror and develop my understanding of anatomy looking at my own reflection. Since I never had the physic, you know, I was not muscle-bound. I imagined myself as one — and that has changed the way how I later looked at human figures and how I now represent them in my work,’ says Shahabuddin, pointing at how he began to eschew representation of real life human figures.

Between reality and human possibility, the thrust in Shahabuddin’s work has always been towards the latter. “Bangladeshis have body-frames that I always exaggerate. I have brought in the drama — otherwise it isn’t painting. In reality you see a lungi-clad man in movement which looks rather weak in a painting,” he adds.

Shahabuddin is also known for his portrayal of Bangabadhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Mahatma Gandhi, leaders he lionizes for their contribution to the emancipation of the masses. In one particular painting, he once put Bangladesh’s two historical figures — Mujib and Bhashani together. The image immediately takes one back to the era when mutual respect could easily supersede the ideological divide.

3

Shahabuddin Ahmed obtained a degree in painting from the Institute of Fine arts in Dhaka before moving to Paris after 1971 at the behest of the Father of the Nation. Paris has been his base ever since. The French government conferred upon him in 2014 their highest civilian title, the much-coveted Chevalier De L’ordre Des Arts Et Des Lettres (Knight in the Order of Fine Arts and Humanities) for his contribution to art.

On the city in which his talent was further nurtured, where he thrived as a painter and held numerous exhibitions over the last 47 or so years, he has a tangle of memories to hark back on. He is conscious of the city’s central role in reshaping art and fashion, trends that began to proliferate on a global scale since the start of 20th century. ‘Whenever you have art you have fashion. In Paris, if you look at Cartier, Pierre Cardin, they are all good draughtsmen. They also mount exhibitions on their drawings from time to time. That Paris holds the key to fashion … did not happen overnight … It all began in the 17th century, with the oligarchs playing a crucial role. Versailles was the centre of many trends and the palace testifies to the cultural firmament. Louvre used to be a palace too,” he points out.

For a painter whose works fetch millions, Shahabuddin seems idealistically opposed to the influence of money. He says, ‘artho or money never helps an artist in his or her creation, but public appreciation does.’ He feels that there are many ways one can earn money, but earning the respect and love of the people what makes one an artist.

Though his career over the last forty or so years follows a steady line of ascent, the maestro still attaches great importance to the need for constant back and forth between minute detail and overall expressiveness. He dubs the detailing as the necessary ‘base’ while the latter reflects the larger vision, which the “function of a relatively bigger engine.” Yet, the process is never mechanical.

‘If you closely observe a footballer, you will find he knows how to play well. But there are moments when he comes up with a move which he did not even know of,’ this indeterminate moment, ‘when an event takes place as if almost on its own,’ is what Shahabuddin waits for when he embarks on a new painting.

“There are two ways [to reach a solution]– one is by making efforts to achieve something and the other by letting the situation take hold of the moment,” he points out. It is the deferral of the latter that keeps playing havoc with the game of painting, at least the kind of painting Shahabuddin Ahmed is into.

Imagination is intrinsic to his game. A Karnatic musician of considerable fame, TM Krisna once said, “The act of imagination is based in simultaneously living the reality of today and intuiting the essence of tomorrow.” This is exactly the framework through which one must look at a Shahabuddin to understand the precariousness associated with the act of painting, especially when adequately greased with emotion. For him the mental activity ignites the ‘performance’ integral to the act of painting. Bodily movements are an essential part of his way of doing paintings.

Shahabuddin Ahmed received the ‘Shadhinota Padak’ in 2000, for his contribution during the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. His artworks are on display in a number of famous museums including Museum of Bourg-en-Bresse (France), National Museum of Bulgaria, Olympic Museum of Lausanne (Switzerland), Seoul Olympic Museum in Republic of South-Korea, National Museum of Taiwan, Bangladesh National Museum and many other galleries.

“I began my career with drawing. Those who have achieved excellence in drawing, for them painting is dangerous. While working on a canvas there appears a tendency to go back to drawing — to bring into the work that perfection one can easily associate with drawing. This too can hold back a painter from freely working towards an indeterminate end,” he says.

“Drawing is important — all big painters are good draughtsmen. But painting has a freedom which makes one transcend good draughtmanship,’ he points out.

At the rooftop studio, during the photo session, Shahabuddin first refuses to strike a pose. After changing into a new red shirt and a pair of shoes, the maestro seems a little more resigned. The ‘aura’ of the persona that was there when he used to appear on the art scene of the early 1980s during his inaugurations, still stays with him. As the shoot takes a little longer than expected, Shahabuddin seems fidgety, and even a bit uncomfortable when the photographer asks him to hold the pose for few more moments as he clicks away.

Few artists are lucky enough to have the kind of relationship Shahabuddin has with his audience. ‘I feel lucky. I never imagined my birthday would be celebrated in such a way. Now, you become conscious of many things, about what you have done, and also what you would be doing in the coming years. I have turned sixty-nine, even I could not even imagine what it means at first,’ he disarmingly declares. The factuality of the last word never weighs down on him since he is eternally seems filled with the same unparalleled enthusiasm for painting as was the case when he was young.

As the camera crew packs their paraphernalia, we receive a parting gift — that hearty smile from the ace painter of the country, whose appeal is treasured by millions.